An elusive international fugitive from justice, cartels, kingpins, stolen passports and the mercenaries who sent him home

By T.D. Griffith

ISLA MARGARITA, VENEZUELA | This Caribbean paradise only a half-hour’s flight from the capital of Caracas served as home and hideout for Dan “Tito” Davis, but it was a world away from his humble beginnings in the sparsely settled state of South Dakota.

As a fugitive from U.S. justice for well over a decade, Davis stayed in the shadows, frequently changed residences in Central and South American countries, avoided English-speaking vacationers, and eventually settled on Isla Margarita with a beautiful wife, a cast of new friends, and a popular kite-surfing resort that he built from scratch on the sandy beaches of his adopted home.

He always knew that a wide array of U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies could eventually track him down, but after a decade he had hoped they’d lost interest. Yet, long before paramilitary forces kidnapped him with a black hood and handguns pointed at his head, Davis sensed his fate had already been decided.

And when the U.S. government employed a highly controversial practice known as rendition, which the United Nations regards as a crime against humanity, his fate was ultimately sealed.

Simple start

Davis was born in Pierre, South Dakota, a remote state capital city that remains one of only two in the U.S. not located on an interstate highway. He grew up in the nearby small town of Onida, the son of “Shorty,” a mechanic, and Marcelleen, a homemaker who later spent 20 years toiling as a janitor at the local school. The hamlet about 25 miles northeast of Pierre was idyllic in the 1960s and early ’70s, when Davis spent his youth riding bicycles in summer and hunting pheasants, geese and deer in the fall.

“It was a great place for kids, no drugs, no crime,” Davis recalled in a recent interview. “You’d ride horses around and the worst thing we ever did was stealing apples, you know?”

That small-town lifestyle changed when Davis moved west to attend Black Hills State University in Spearfish. In his 18-month stint at the college, he didn’t pay much attention to his classes, but he did discover that selling white-cross pep pills to classmates paid extremely well.

Over time, living in a remote, sparsely populated region where people were out-numbered by ponderosa pines, cattle and free-roaming herds of mule deer, Davis realized he needed to find a larger market.

“It was kind of boring and I could see I needed to do more in life than hang out in the Black Hills,” he said. “It was so cold.”

So he moved to the desert and transferred his college credits to the University of Nevada-Las Vegas. The town wasn’t then the gambling mecca and sin city we know today, Davis said. With a population hovering around 200,000, Vegas was safe, he said, the kind of community where you could leave your keys in your car and not worry about a thief driving off with it.

“The mob was running the town,” he said. “It was a small-town environment. Glenn Campbell and Donna Summer would speak at our college classes, then give us tickets to their shows.”

Trading in legal drugs

But Davis wasn’t interested in late-night dancing to the latest disco hits. He was concentrating on taking his legal drug dealing to the next level. After unsuccessful experiments with pill presses in his own home, Davis founded Pucci Pet Products, a cover, and soon had pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly manufacturing millions of then-legal ephedrine pills, which he then distributed nationwide with the help of contacts in the Bandidos Motorcycle Club.

“When it was really rolling, we were selling millions of pills a week,” Davis said. “My cut was about $200,000 a week. We had a helluva market because we had the product — no chipped pills — these were professionally made.”

Soon Davis was living the high life, a 24-year-old married to the daughter of a prominent Rapid City, S.D., family, sporting gold and diamond “bling,” buying luxury homes and classic cars, and investing in apartment complexes and real estate developments. At one point, he owned a flight school and three or four airplanes, giving him cover and making it easier to transport his wares anywhere in the country.

Busted

Eventually, Davis pleaded guilty to tax evasion and illegal use of a telephone, was sentenced to 102 months in a federal prison, and had virtually everything he had accumulated seized. Six days after his first child was born, Davis was sent to prison, where he would spend “a nickel,” or a five-year stint.

Divorced by his first wife just weeks before being released from prison, Davis returned to South Dakota and worked 7 a.m. to midnight seven days a week with his mother at a small ice cream parlor in Keystone, a tourist town located in the shadows of Mount Rushmore National Memorial. When winter came and the shops closed, he returned to Las Vegas, fell in love, married the daughter of a wealthy family and returned to his former habits.

After reconnecting with his Mexican marijuana suppliers, within 18 months he was clearing $50,000 a week. Learning from his earlier experience with the feds, Davis began stashing cash in a Mexico City bank, later saying “it was the wisest move that I ever made.”

Reluctantly, Davis said he began fronting his product to an old grade-school chum. When the feds arrested that childhood friend with $28,000 in cash and 2 ounces of meth, Davis said the guy “folded like a Texas Hold ‘Em player with an off-suit deuce-seven” and gave Davis up to authorities, lying that he had supplied the meth.

Soon arrested again on felony drug charges tied to his friend’s erroneous testimony, Davis spent 63 days in a Deadwood jail before being released on bond shortly before his scheduled trial.

“My attorney said it wasn’t looking good and commented that he couldn’t believe I was still here,” Davis said. “I was looking at 30 years in a federal facility, which would have basically meant life in prison.”

So he fled.

Life on the run

Taking a flight from Denver to the Mexican border, Davis jumped on a train and spent months in small towns in Mexico’s interior, avoiding coastal resorts populated by sun-seeking Americans, and hiring private tutors to teach him Spanish. At 40 years old, Davis said his knowledge of the native language didn’t initially extend beyond the cursory greeting of “hola.”

He was ever watchful, abandoning a town if he spotted someone too well-dressed for their surroundings, or after encountering anyone who asked him one too many questions. Fortunately, he said his stashed cash generated friendships and helped him avoid Mexican federales.

“You’re not going to make much of an impression coming into Mexico City with a backpack,” he said. “I had stashed money out of country because if something went wrong, at least I might have a chance. I was the gringo picking up the tab, not a parasite running around.”

Assumed identities

For the next 13 years, Davis explored the world using various forged or stolen passports, visiting 54 countries on five continents, always looking over his shoulder and always avoiding Americans. He watched camel races in India, visited base camps at the foot of Mount Everest, toured Cuba, Germany, Vietnam and the Philippines and spent a year on the Amazon River in Brazil.

Asked how much cash he had funneled into banks out of the country, Davis said matter-of-factly, “I could have gone through $100,000 a year for many years and never run out. I learned the first time — putting stuff in my own name, planes, houses, cars, and the IRS grabbed all of it.”

With no permanent residence, no real love in his life, infrequent contacts with friends of the past, and living under numerous assumed identities, Davis said at times he felt lost.

“I walked into a bank one time with three stolen IDs,” he recalled. “I was afraid the bank would run the numbers on my passport and find it was reported stolen. I went to sign for a safety deposit box and I signed the wrong name because I forgot who I was. I was lucky so many times.”

One last love

Eventually, Davis found a new home and a new love in Venezuela, in the form of a 5-foot-11 beauty queen and world-class volleyball player named Mary Luz. After an uneven courtship and worldwide travel, the two married and settled in a small seaside town called El Yaque, popular for its kite-surfing. There, Davis bought land and began constructing a resort catering to rich Europeans. He poured years into the project and was nearly done when the day he knew would come finally came.

As he strode through his resort near his Wind Guru Café early one evening in the spring of 2007, Davis noticed several large men in slacks and dress shirts, decidedly out of place on a beach where everyone wore shorts and T-shirts. Moments later, he spotted black Suburbans with blacked-out windows parked nearby.

“At that moment I knew it was over,” he said. “I couldn’t tell if they were working for a drug cartel, a government or somebody else. At that moment it really didn’t matter.”

Tackled and tied, pistols pointed at his head, which was soon covered with a black nylon bag, Davis was thrown into a vehicle and whisked away. He would spend a week in guarded rooms, handcuffed to the top bunk, being repeatedly interrogated and photographed. And he would never see Mary Luz again.

“I didn’t listen to my stomach,” he said in a moment of introspection. “I was living in Venezuela with the love of my life, a wonderful wife, and feeling like the mayor of the town. It was too good to be true. I thought, `They’re not going to be looking for me.’ But I was wrong.”

Homeward bound

After five days in a mountaintop cell, Davis was unceremoniously told, “You’re going to the United States.” Although Venezuela had no extradition treaty with the U.S., (then or now), and its president, Hugo Chavez had a contentious relationship with then-President George W. Bush, calling him “the devil” before the United Nations, Davis said his mercenary captors had made a deal and he was quickly flown to Miami and handed off to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Venezuelan authorities seized Davis’ entire resort, put Mary Luz and her 94-year-old mother on the street, confiscated her wedding ring and hauled away everything that would move, all the way down to the light bulbs in his luxury beachfront penthouse.

Despite the lack of any extradition treaty with the U.S., Venezuelan mercenaries not only kidnapped Davis and seized everything he owned, but entangled his Venezuelan attorneys in legal cases that would take years to unravel.

Extraordinary rendition

U.S. law enforcement would use a rare and controversial practice known as rendition to return Davis to face justice. Rendition traces its origins to the mid-1800s, when it was used to recapture fugitive slaves who, under the U.S. Constitution, held virtually no human rights.

Perhaps the most famous early case of irregular or extraordinary rendition was tied to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, when U.S. authorities returned John Surratt, a suspected co-conspirator, to America in 1866, after Surratt had fled to Egypt.

Surratt was the son of convicted Lincoln conspirator, Mary Surratt. But unlike his mother and eight other individuals who were eventually hanged for killing Lincoln, John Surratt escaped any punishment for his role in the murder, according to Rebecca Beatrice Brooks, whose 2011 article, “John Surratt: The Lincoln Conspirator Who Got Away,” documented the case.

“The prosecution had little evidence against Surratt and the case eventually ended in a mistrial when the jury could not reach a verdict,” Brooks wrote.

Legal journals define extraordinary or forced rendition as, “the transfer of a prisoner or suspect from one country to another, often to avoid legal restrictions on interrogation or prosecution.” Other sources describe it as “government-sponsored abduction and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to another.”

President Bill Clinton authorized extraordinary rendition to nations know to practice torture, while President George W. Bush rendered hundreds of so-called illegal combatants for torture by proxy, exposing the suspects to programs under which they suffered from the euphemistic practice known as enhanced interrogation.

Rendition violates United Nations’ conventions and the organization considers one nation abducting the citizens of another a crime against humanity. Its legality remains highly controversial.

Tito’s case

But in the case of Dan “Tito” Davis, attorneys familiar with the case contend his kidnapping and the seizure of his Venezuelan assets – which they valued at more than $10 million – were simply a case of unbridled greed.

“If a government guy walks by your house and he likes it, he takes it,” said a longtime Venezuelan attorney now living in Miami who, fearing retribution from authorities, spoke on condition of anonymity. “It’s hard for people in the U.S. to understand that, but that’s the way it is.”

The 52-year-old attorney who handled Davis’ property deals and resort development, felt the full force of the Venezuelan government following his client’s kidnapping.

“Every police force in the country showed up at my office, which was the address of his (Davis’) company,” the lawyer said. “They took all the files from my office, took over my office and detained everyone including my father. It was a mess, because his situation went on for like three years and many things are still not resolved.

“Part of my office is still seized by the government, even though I have a court order they says they have to release my office,” he added. “One part of my office is still in the hands of the government.”

Even though more than a decade has passed since his life and that of his client were disrupted, the attorney said neither of them expects any resolution as long as the current administration of Nicolas Maduro remains in power. Maduro has been president since 2013, after serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Vice President under Chavez.

“They have taken most of my land, my building, a shopping mall, tens of millions of dollars,” the attorney said. “It’s very tough. I used to go back to Venezuela every month, but now it’s every three or four months. I now try to avoid going to Venezuela because it makes me very sad.”

The attorney said he still regrets the injustice his client experienced at the hands of his government.

“They had a grudge against Tito, that’s the only thing I can figure,” he said. “It’s not like he killed anybody.

“Everything about Tito’s case is unusual,” the attorney added. “It was super unfair what happened to him. This was not drug money, he’s not a terrorist and he committed no crimes in Venezuela, so why keep it? With a fair judicial system, he would be in Venezuela now and be doing business.

“He built a great resort with attention to every detail. It was just beautiful and that’s why they will not return it. The head of anti-drug investigations in Venezuela made Tito’s 8,500-square-foot penthouse his penthouse.”

A second Venezuelan attorney who assisted Davis with corporate affairs and real estate transactions, lamented the corruption inherent in his country’s current government and what that means to anyone living or attempting to do business in Venezuela. He, too, spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing reprisal.

“It’s a very corrupt and very inefficient system,” he said. “It’s a money trap. You get involved in a circle of extortion. Every move you make you have to pay off somebody or you will be railroaded. It’s governed by different mafias and they all have their territories. They are called tribes and there’s even one called the Midgets.”

Recognizing the system is highly corrupt, the attorney said he was surprised that authorities acted so aggressively in Davis’s case, suggesting his client may have been “the lamb offered for something else.”

“At the time, Venezuelan authorities were being pressed by the U.S. that they weren’t being aggressive with drugs, even being accused of being involved in the drug trade themselves,” he said. As evidence, the attorney said it’s often difficult to differentiate between cops and criminals in Venezuela, because they can be both.

“They will not charge you,” he said. “You will get mugged or kidnapped and you will end up dead. That’s what happens here and it happens a lot. You’ll end up dead in a ditch. These guys are beasts.”

The veteran attorney, whose office also was seized following the arrest of his client, said the procedures the government employed in kidnapping Davis and confiscating all his assets would never stand up to review under the U.S. judicial system.

“The U.S. prides itself in being harsh on application of its law, but things have to be done right,” he noted. “If this went to a U.S. court, some shit would hit the fan. If the U.S. is using enforcement agencies in support of our military dictatorship and drug-related forces, where does it end? There is generally a process for extradition and it involves courts with all the legal guarantees.

“In this case, they acted like Tito was Al Pacino in `Scarface,’” he said.

The Wild West

While the life of Dan Davis has had as many turns as that of Tony Montana in Oliver Stone’s classic film, Tito, as his friends refer to him, is hoping for a better outcome.

Davis grew up in the real Wild West, not far from the graves of Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane and a wild and woolly gold-rush town known as Deadwood, where some claim there once was a death a day due to unnatural causes.

He says he returned to the Wild West in Venezuela, where the lawmen were as suspect as the cartels’ gunmen, and the government remains on the dole.

“One day, I’m living the life with a wonderful wife in a South American paradise,” he said. “Then I was black-bagged and it’s never been the same. I woke up in a cell in Miami with a soggy roll of toilet paper as a pillow and a guy urinating next to my head.”

Looking back on his life on the lam and three marriages interrupted by the law, Davis said his only real regret remains leaving those loves in his tracks.

“I lost three perfectly good wives, that’s the truth,” he said. “I loved every one of them, but I lost them because of the wrong decisions.”

Reclaiming life

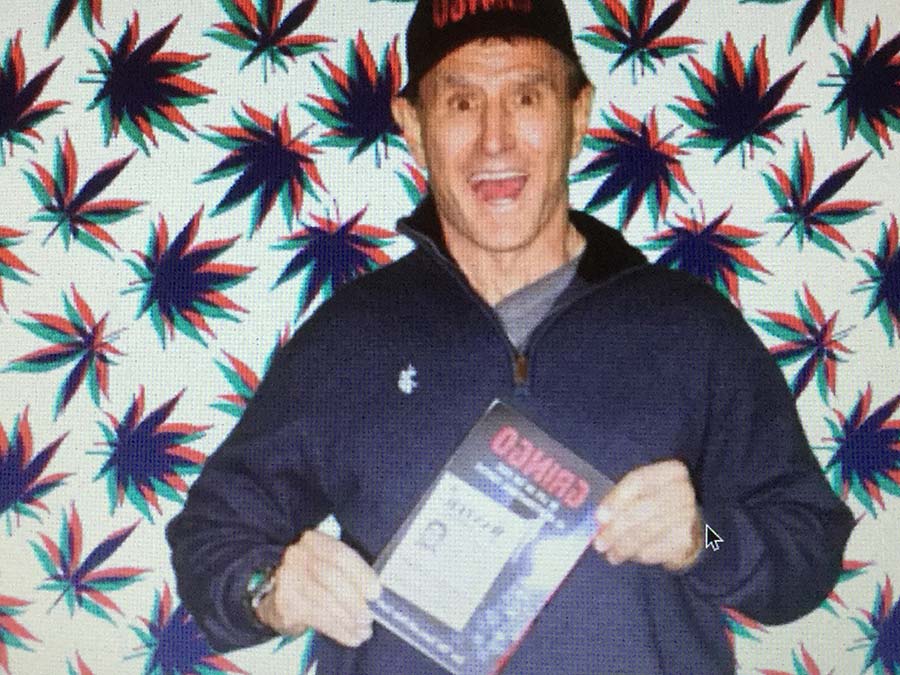

Released from prison in October 2015, Davis will remain on probation through the end of this year. When he is in the U.S., Davis lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Key West, Florida, where nearby bungalows start at $1 million.

But in recent months, he’s caught up with old friends by traveling to China, Thailand, the Philippines and South Africa. Those adventures are more enjoyable today, he says, because he’s not constantly checking his back.

“I’m playing some pickle ball, riding my bike, working out, trying to stay healthy and make up for all the years of things I missed,” he said. “It’s wonderful being a normal citizen.

“My past is fun talking about now, but when you spent so much time as an international fugitive from justice and looking over your shoulder, it’s not good.”

___________________________________

T.D. Griffith has written or co-authored more than 70 books and his features have been published by more than 250 magazines and newspapers from New York to New Zealand.

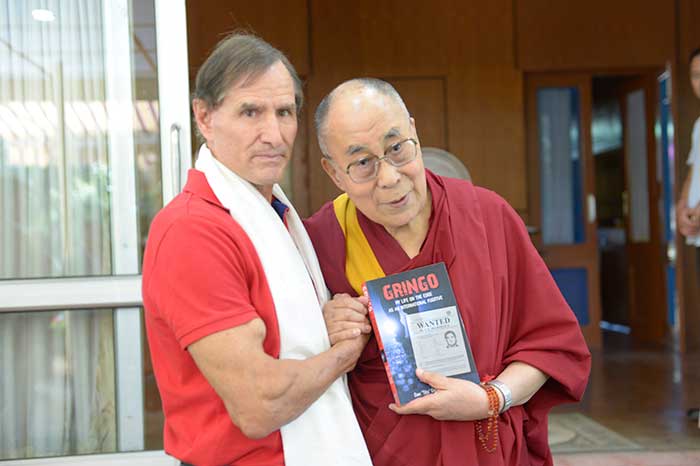

Dan “Tito” Davis has written a book about his experiences on the run called “Gringo: My Life on the Edge as an International Fugitive”

Leave A Comment